Report from Captain T. H. Lindemann, of the ship Governor General Loudon, anchored at Telok Betong

Monday, August 27th. Finding that at midnight on the evening of our arrival [Aug. 26, 7:30 p.m.] there was still no boat come off to us from the shore, and as the weather was now much calmer, I sent the first mate in the gig with a crew of six men to find out what was the reason of this. About 1 a.m. he returned, and stated that it had been impossible to land on account of the heavy current and surf; also that the harbour pier-head stood partly under water.

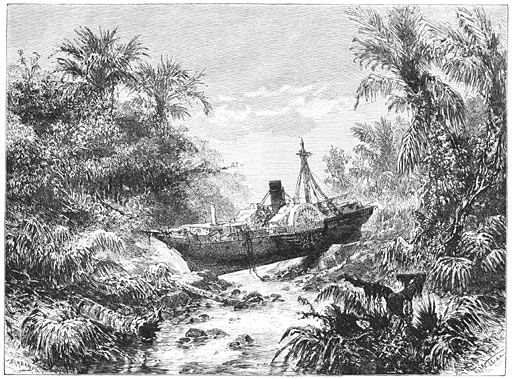

The Government steamer Berouw, which lay anchored near the pier-head, hailed the mate as he was returning on board, and the people on board her then stated to him that it was impossible to land anywhere, and that a boat which had put off from the shore had already been wrecked. That by 6 p.m. on Sunday evening it had already begun to be stormy, and that the stormy weather had been accompanied by a current which swept round and round (apparently a sort of whirlpool). When the mate had come on board, we resolved to await daylight before taking any further steps; however, for the sake of security, we steamed several ships' lengths outwards, because the sound of a ship's bell which seemed to be approaching us made us suspect that the ship must be adrift, and wishing therefore to avoid a collision we re-anchored in nine fathoms with thirty fathoms shackle outside the hawsepipe. We kept the ordinary sea-watch, and afterwards heard nothing more of the bell. When day broke, it appeared to us to be still a matter of danger to send a boat ashore; and we also discovered that a revenue cutter was foul of a sailing-vessel which lay in the roadstead, and that the Berouw was stranded. However, owing to the violent winds and currents, we did not dare to send a boat to her assistance.

About 7 a.m. we saw some very high seas, presumably

an upheaval of the sea, approaching us up the roadstead.

These seas poured themselves out upon the shore and

flowed inland, so that we presumed that the inhabitants who

dwelt near the shore must be drowned. The signal beacon

was altogether carried away, and the Berouw then lay high

upon the shore among the cocoanut trees. Also the revenue

cutter lay aground, and some native boats which had been

lying in the neighborhood at anchor were no more to be

seen.

Since it was very dangerous to stay where we were, and since if we stayed we could render no assistance, we concluded to proceed to Anjer under steam, and there to give information of what had taken place, weighed anchor at 7:30 a.m., and following the direction of the bay steered thereupon southwards. At 10 a.m. we were obliged to come to anchor in the bay in 15 fathoms of water because the ash rain kept continually growing thicker and thicker, and pumice-stone also began to be rained, of which some pieces were several inches thick. The air grew steadily darker and darker, and at 10:30 a.m. we were in total darkness, just the same as on a very dark night. The wind was from the west-ward, and began to increase till it reached the force of a hurricane. So we let down both anchors and kept the screw turning slowly at half speed in order to ride over the terribly high seas which kept suddenly striking us presumably in consequence of a "sea quake," and made us dread being buried under them.

Awnings and curtains from forward right up the main-mast, three boat covers, and the uppermost awning of the quarter deck were blown away in a moment. Some objects on desk which had been lashed got loose and were carried overboard; the upper deck hatchways and those on the main deck were closed tightly, and the passengers for the most part were sent below. Heavy storms. The lightning struck the mainmast conductor six or seven times, but no damage. The rain of pumice-stones changed to a violent mud rain, and this mud rain was so heavy that in the space of ten minutes the mud lay half a foot deep.

Kept steaming with the head of the ship as far as possible seawards for half an hour when the sea began to abate, and at noon the wind dropped away entirely. Then we stopped the engine. The darkness however remained as before, as did also the mud rain."